It's not you. HDR confuses tons of people.

Last year we announced HDR or "High Dynamic Range" photography was coming to our popular photography app, Halide. While most customers celebrated, some were confused, and others showed downright concern. That's because HDR can mean two different, but related, things.

The first HDR is the "HDR mode" introduced to the iPhone camera in 2010.

The second HDR involves new screens that display more vibrant, detailed images. Shopped for a TV recently? No doubt you've seen stickers like this:

This post finally explains what HDR actually means, the problems it presents, and three ways to solve them.

What is Dynamic Range?

Let's start with a real world problem. Before smart phones, it was impossible to capture great sunsets with point-and-shoot cameras. No matter how you fiddled with the dials, everything came out too bright or too dark.

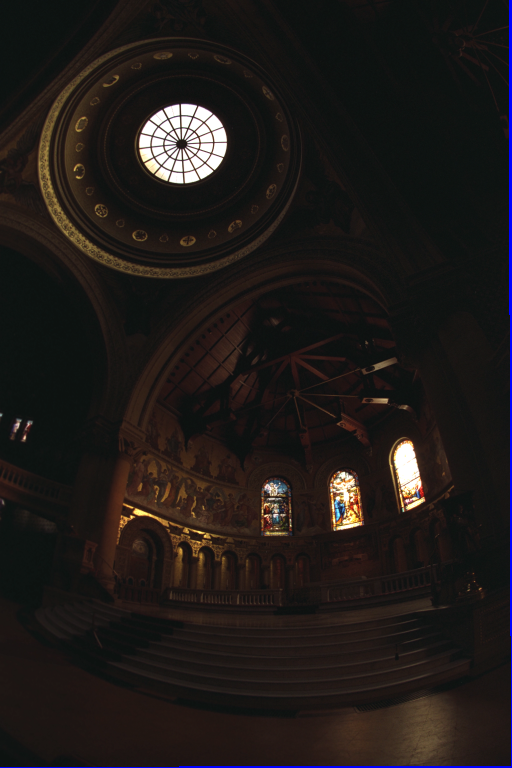

The result of trying to capture a sunset with an old-school camera.

In that photo, the problem has to do with the different light levels coming from the sky and the buildings in shadow, the former emitting thousands of times more light than the latter. Our eyes can see both just fine. Cameras? They can deal with overall bright lighting, or overall dim lighting, but they struggled with scenes contain both really dark and really bright spots.

Dynamic range simply means, "the difference between the darkest and brightest bits of a scene." For example, this foggy morning is an example of a low dynamic range scene, because everything is sort of gray.

Most of our photos aren't as extreme as bright sunsets or foggy mornings. We'll just call those "standard dynamic range" or SDR scenes.

Before we move on, we need to highlight that the HDR problem isn't limited to cameras. Even if you had a perfect camera that could match human vision, most screens cannot produce enough contrast to match the real world.

Regardless of your bottleneck, when a scene contains more dynamic range than your camera can capture or your screen can pump out, you lose highlights, shadows, or both.

Solution 1: "HDR Mode"

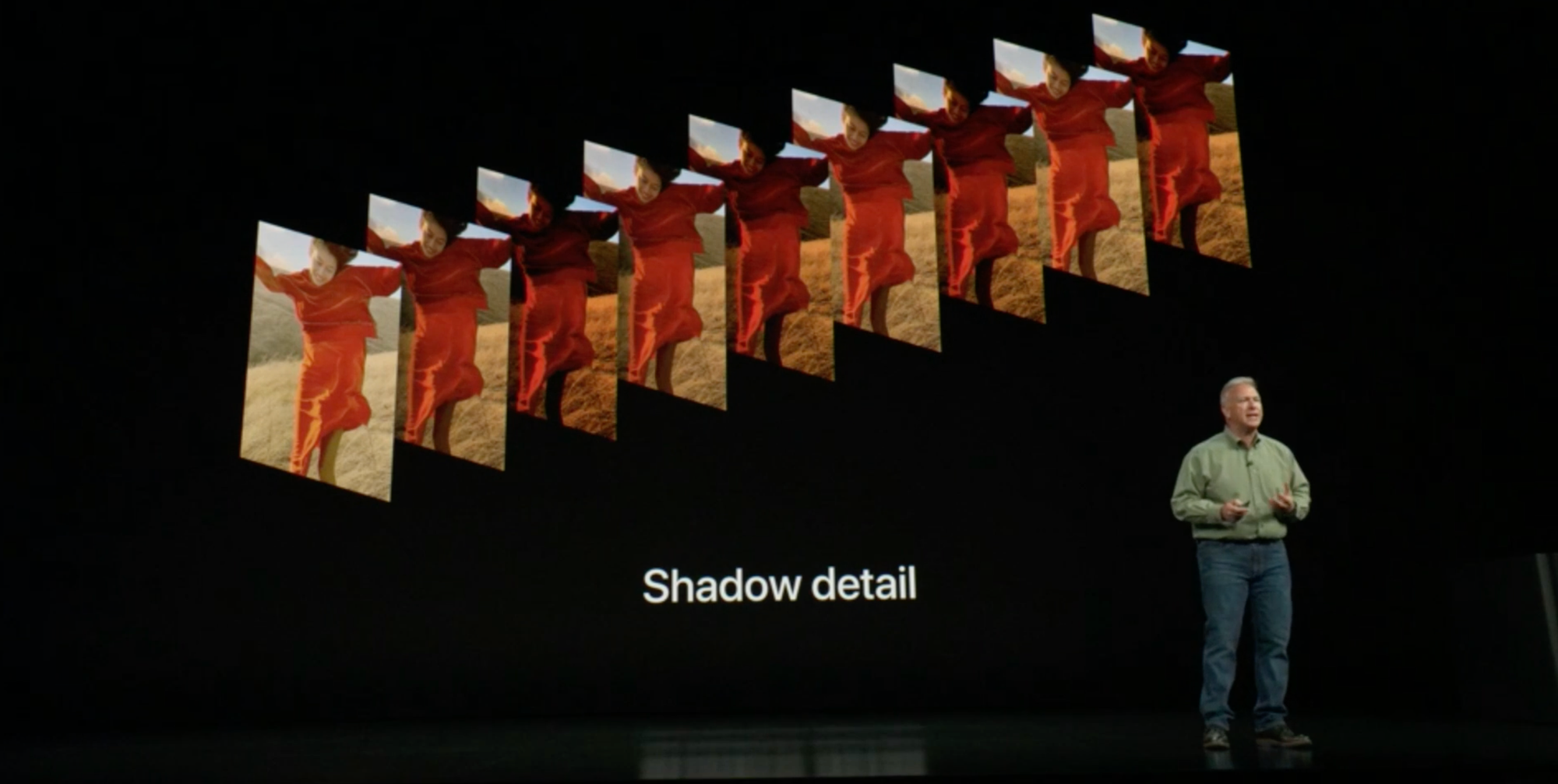

In the 1990s researchers came up with algorithms to tackle the dynamic range problem. The algorithms started by taking a bunch of photos with different settings to capture more highlights and shadows:

This full sequence has 16 photos. Via Paul Debevec.

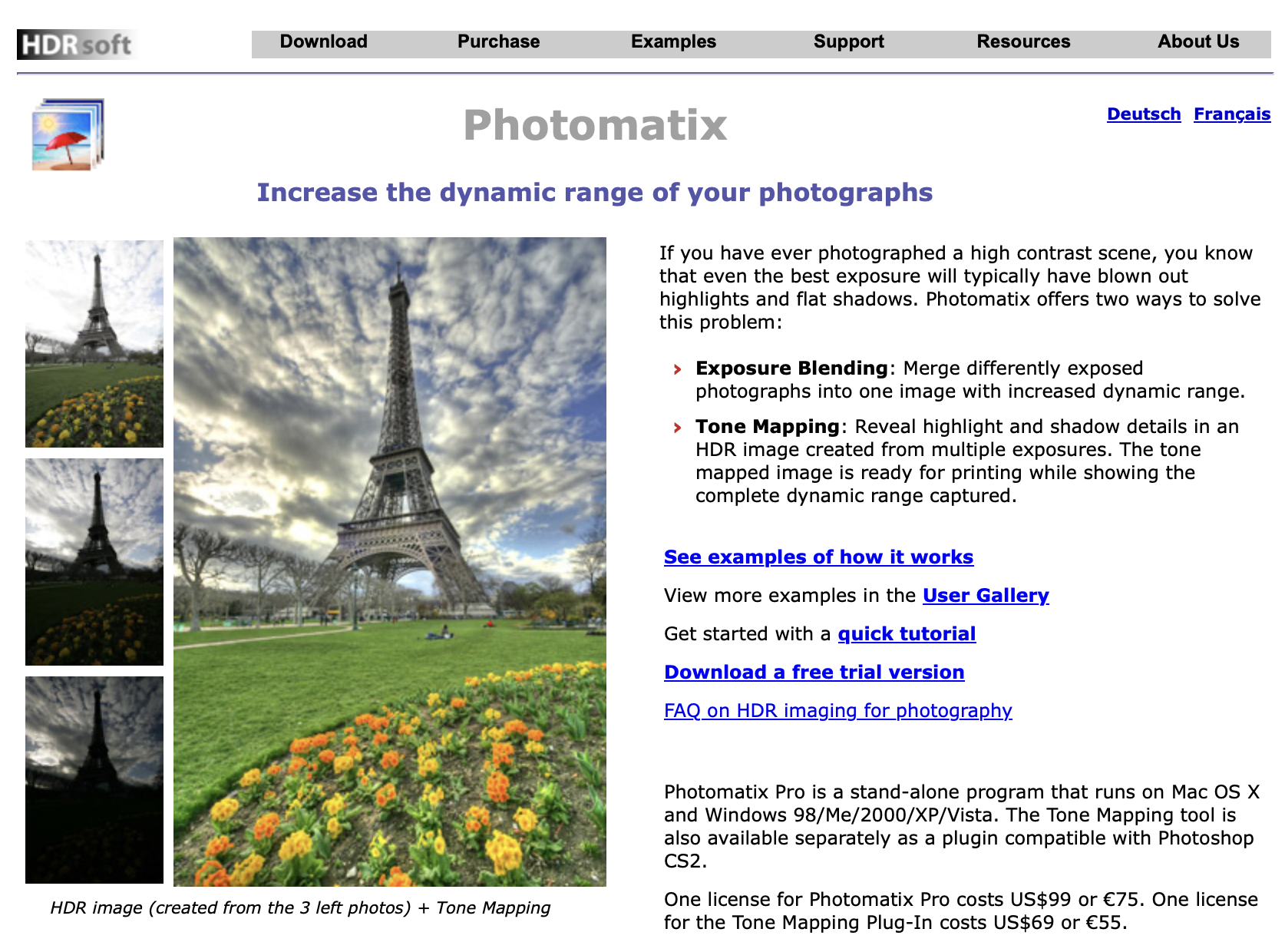

Then the algorithms combined everything into a single "photo" that matches human vision… a photo that was useless, since computer screens couldn't display HDR. So these researchers also came up with algorithms to squeeze HDR values onto an SDR screen, which they called "Tone Mapping."

These algorithms soon found their way into commercial software for camera nerds.

Unfortunately, these packages required a lot of fiddling, and too many photographers in the mid-2000s… lacked restraint.

Taste aside, average people don't like fiddling with sliders. Most people want to tap a button and get a photo that looks closer to what they see without thinking about it. So Google and Apple went an extra step in their camera apps.

Your modern phone's camera first captures a series of photos at various brightness levels, like we showed a moment ago. From this burst of photos, the app calculates an HDR image, but unlike that commercial software from earlier, it uses complex logic and AI to make the tone mapping choices for you.

Apple and Google called this stuff "HDR" because "HDR Construction Followed By Automatic Tone Mapping" doesn't exactly roll off the tongue. But just to be clear, the HDR added to the iPhone in 2010 was not HDR. The final JPEG was an SDR image that tries to replicate what you saw with your eyes. Maybe they should have called it "Fake HDR Mode."

I know quibbling over names feels as pedantic as going, "Well actually, 'Frankenstein' was the doctor, you're thinking of 'Frankenstein's Monster,'" but if you're going to say you hate HDR, remember that it's bad tone mapping that is the actual monster. That brings us to…

The First HDR Backlash

Over the years, Apple touted better and better algorithms in their camera, like Smart HDR and Deep Fusion. As this happened, we worried that our flagship photography app, Halide, would become irrelevant. Who needs a manual controls when AI can do a better job?

We were surprised to watch the opposite play out. As phone cameras got smarter, users asked us to turn off these features. One issue was how the algorithms make mistakes, like this weird edge along my son Ethan's face.

That's because Smart HDR and Deep Fusion require that the iPhone camera capture a burst of photos and stitch them together to preserve the best parts. Sometimes it goofs. Even when the algorithms behave, they come with tradeoffs.

Consider these photos I took from a boat in the Galapagos: the ProRAW version, which uses multi-photo algorithms, looks smudgier than the single-shot capture I took moments later.

Left: Merged from Multiple Photos. Right: A single exposure.

What's likely happening? When things move in the middle of a burst capture— which always happens when shooting handheld— these algorithms have to nudge pixels around to make things line up. This sacrifices detail.

Since 2020, we've offered users the option of disabling Smart HDR and Deep Fusion, and it quickly became one of our most popular features.

This lead us to Process Zero, our completely AI-free camera mode, which we launched last year and became a smash hit. However, without any algorithms, HDR scene end up over and under exposed. Some people actually prefer the look — more on that later — but many were bummed. They just accepted this as a tradeoff for the natural aesthetic of AI-free photos.

But what if we don't need that tradeoff? What if I told you that analog photographers captured HDR as far back as 1857?

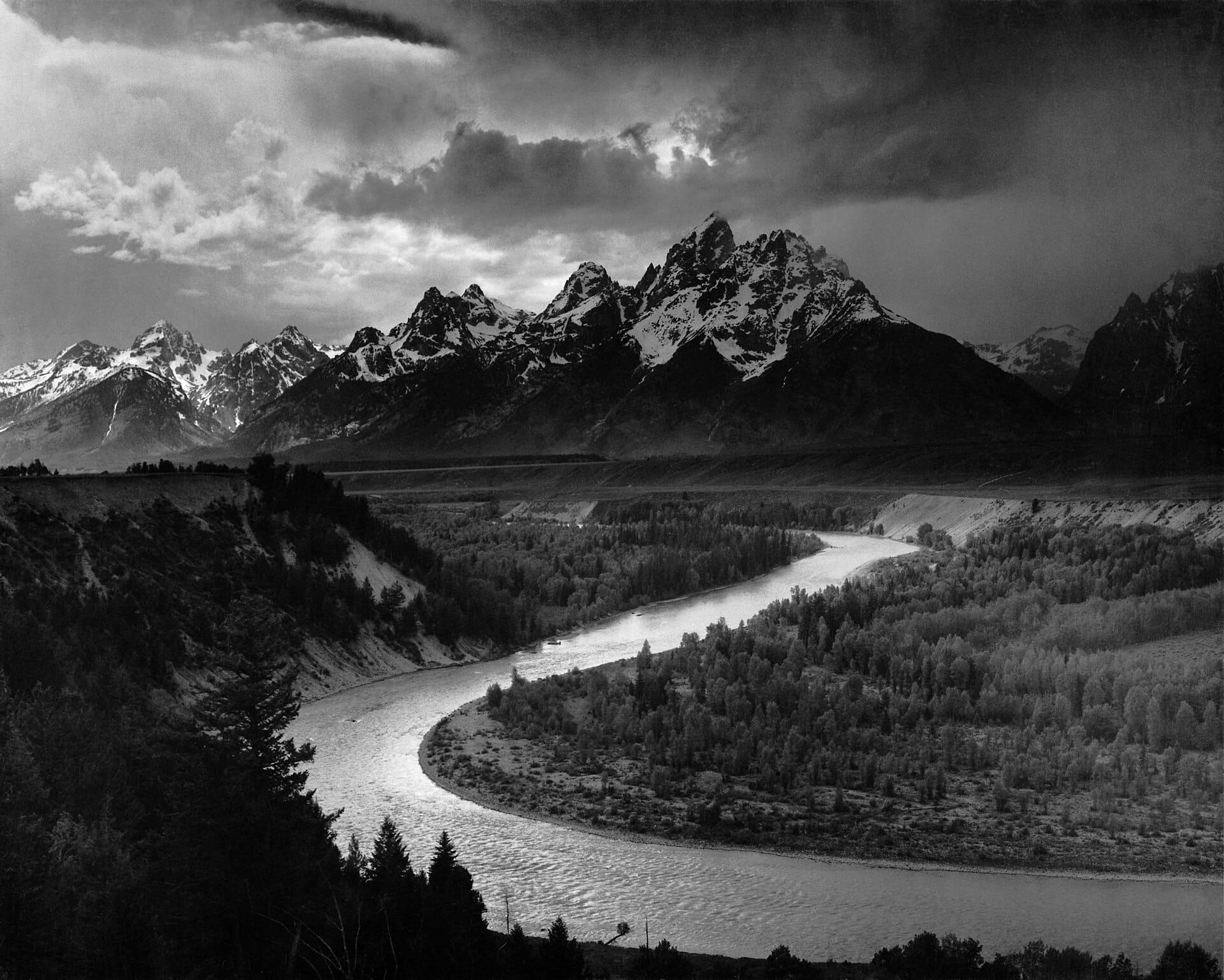

Ansel Adams, one of the most revered photographers of the 20th century, was a master at capturing dramatic, high dynamic range scenes.

It's even more incredible that this was done on paper, which has even less dynamic range than computer screens!

From studying these analog methods, we've arrived at a single-shot process for handling HDR.

How do we accomplish this from a single capture? Let's step back in time.

Learning From Analog

In the age of film negatives, photography was a three step process.

- Capture a scene on film

- Develop the film in a lab

- Transfer the film to paper

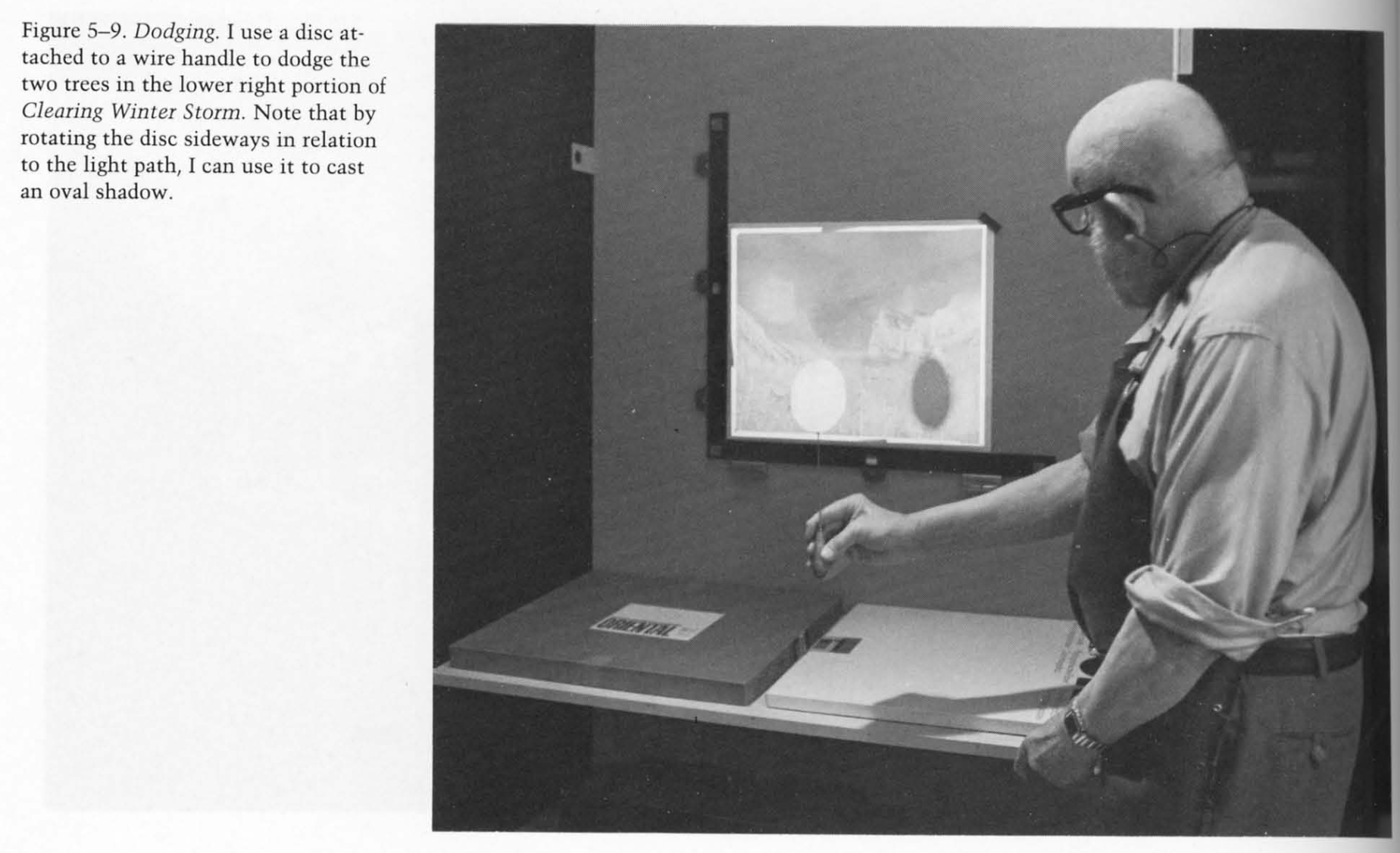

It's important to break down these steps because— plot twist— film is actually a high dynamic range medium. You just lose the dynamic range when you transfer your photo from a negative to paper. So in the age before Photoshop, master photographers would "dodge and burn" photos to preserve details during the transfer.

Is it a lie to dodge and burn a photo? According to Ansel Adams in The Print:

When you are making a fine print you are creating, as well as re-creating. The final image you achieve will, to quote Alfred Stieglitz, reveal what you saw and felt.

I'm inclined to agree. I don't think people reject processing your photos, whether it's dodging-and-burning a print, or fiddling with multi-exposure algorithms. The problem is that algorithms are not artists.

AI cannot read your mind, so it cannot honor your intent. For example, in this shot, I wanted stark contrast between light and dark. AI thought it was doing me a favor by pulling out detail in the shadow, flattening the whole image in the process. Thanks Clippy.

Same lighting, moments apart. Left: Process Zero. Right: the iPhone camera's automatic tone mapping.

Even when tone mapping can help a photo, AI may take things too far, creating hyper-realistic images that exist in an uncanny valley. Machines cannot reason their way to your vision, or even good taste.

We think there's room for a different approach.

A Different Approach: Opt-In, Single Shot Tone Mapping

After considerable research, experimentation, trial and error, we've arrived on a tone mapper that feels true to the dodging and burning of analog photography. What makes it unique? For starters, it's derived from a single capture, as opposed to the multi-exposure approaches that sacrifice detail. While a single capture can't reach the dynamic range of human vision, good sensors have dynamic range approaching film.

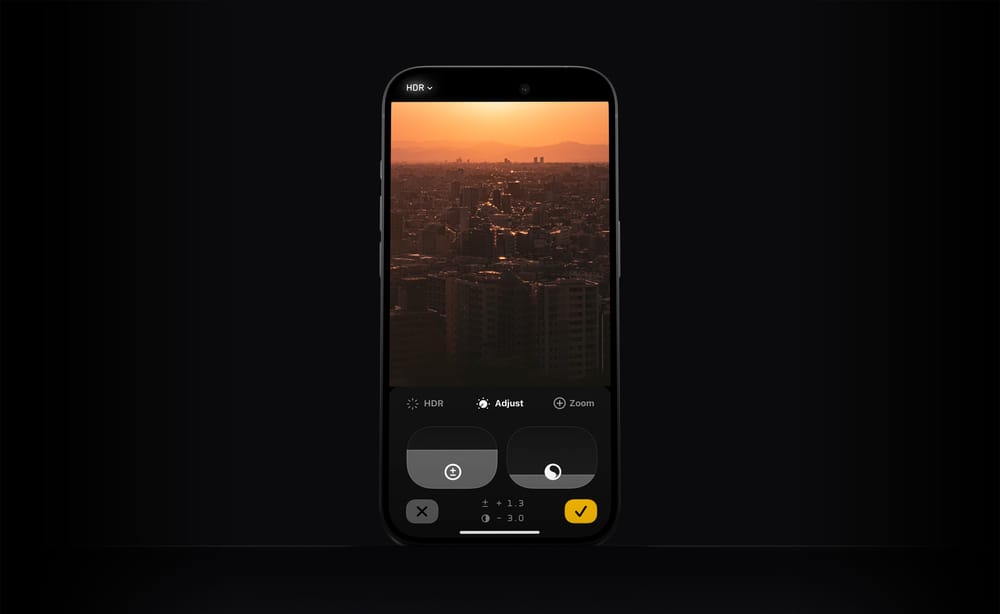

However, the best feature is that this tone mapping is off by default. If you come across a photo that feels like it could use a little highlight or shadow recovery, you can now hop into Halide's updated Image Lab.

In the Image Lab we have an exposure slider for adjusting overall brightness just like before. But to its right, we have a single dial that tames or boosts dynamic range. We think it's up to the photographer to decide what feels right.

To be clear, the tone mapper works different than simply bringing your photo into an editor and dragging the "shadows" and "highlights" sliders. It also does it best to preserve local contrast.

Left and Middle: a shot with simple exposure adjustments. Right: a tone-mapped version.

Don’t worry: adjusting this stuff after-the-fact won't sacrifice quality. Since Halide captures DNG or "digital negative" files, it contains all of the information that your screen cannot display. The shadow and highlight details are already in there, and the tone-mapping simply brings it out selectively.

Solution 2: Genuine HDR Displays

I went to all that trouble explaining the difference between HDR and Tone Mapping because… drum roll please… today's screens are HIGHer DYNAMIC RANGE!

The atrium of the Hyatt Centric in Cambridge

Ok, today's best screens still can't match the high dynamic range of real life, but they're way higher than the past. Spend a few minutes watching Apple TV's mesmerizing screensavers in HDR, and you get why this feels as big as the move from analog TV to HDTV. So… nine years after the introduction of HDR screens, why hasn't the world moved on?

A big problem is that it costs the TV, Film, and Photography industries billions of dollars (and a bajillion hours of work) to upgrade their infrastructure. For context, it took well over a decade for HDTV to reach critical mass.

Another issue is taste. Much like adding a spice to your meal, you don't want HDR to overpower everything. The garishness of bad HDR has left many filmmakers lukewarm on the technology. Just recently, cinematographer Steve Yedlin published a two hour lecture on the pitfalls of HDR in the real world.

If you want to see how bad HDR displays can get, look no further than online content creators. At some point these thirsty influencers realized that if you make your videos uncomfortably bright, people will pause while swiping through their Instagram reels. The abuse of brightness has lead to people disabling HDR altogether.

For all these reasons, I think HDR could end up another dead-end technology of the 2010s, alongside 3D televisions. However, Apple turned out to be HDR's best salesperson, as iPhones have captured and rendered HDR photos for years.

In fact, after we launched Process Zero last year, quite a few users asked us why their photos aren't as bright as the ones produced by Apple's camera. The answer was compatibility, which Apple improved with iOS 18. So HDR is coming to Process Zero!

To handle the taste problem, we're offering three levels of HDR:

- Standard: increases detail in shadows, and bumps up highlights while giving a tasteful rolloff in highlights

- Max: HDR that pushes the limits of the iPhone display

- Off: turns HDR off altogether.

Compatibility Considerations

Once you've got an amazing HDR photo, you're probably wondering where you can view it, today. The good news is that every iPhone that has shipped for the last several years supports HDR. It just isn't always available.

As we mentioned earlier, some users turn off HDR because the content hurts their eyes, but even if it's on, it isn't always on. Because HDR consumes more power, iOS turns it off in low-power mode. It also turns it off when using your phone in bright sunlight, so it can pump up SDR as bright as it can go.

An even bigger issue is where you can share it online. Unfortunately, most web browser can't handle HDR photos. Even if you encode HDR into a JPEG, the browser might butcher the image, either reducing the contrast and making everything look flat, or clipping highlights, which is about as ugly as bad digital camera photos from the 1990s.

But wait… how did I display these HDR examples? If you look carefully those are short HDR videos that I've set to loop. You might need these kinds of silly hacks to get around browser limitations.

Until recently, the best way to view HDR was with Instagram's native iPhone app. While Instagram is our users' most popular place to share photos… it's Instagram. Fortunately, things are changing.

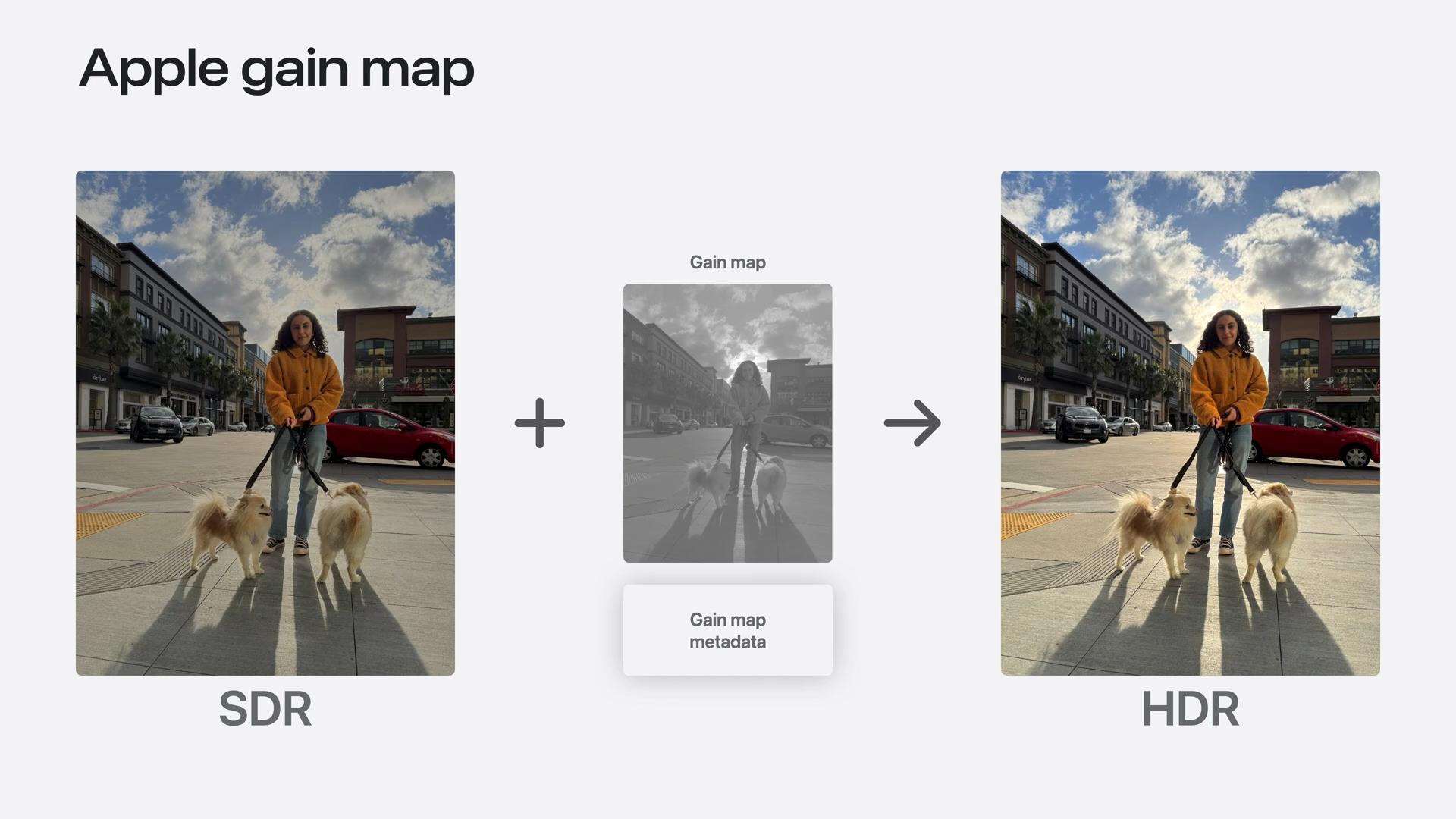

iOS 18 adopted Adobe's approach to HDR, which Apple calls "Adaptive HDR." In this system, your photos contain both SDR and HDR information in a single file. If an app doesn't know what to do with the HDR information, or it can't render HDR, there's an SDR fallback. This stuff even works with JPEGs!

Browser support is halfway there. Google beat Apple to the punch with their own version of Adaptive HDR they call Ultra HDR, which Android 14 now supports. Safari has added HDR support into its developer preview, then it disabled it, due to bugs within iOS.

Speaking of iOS bugs, there's a reason we aren't launching the Halide HDR update with today's post: HDR photos sometimes render wrong in Apple's own Photos app! Oddly enough, they render just fine in Instagram and other third-party apps. We've filed a bug report with Apple, but due to how Apple releases software, we doubt we'll see a fix until iOS 19.

Rather than inundate customer support with angry emails about how photos don't look right in Apple's photos app, we've decided to release HDR support in our Technology Preview beta that we're offering to 1,000 Halide subscribers. Why limit it to 1,000? Apple restricts how many people can sign up for TestFlight, so we want to make sure we stay within our limits. This is the start of our preview of some very exciting big features in Halide which are part of our big Mark III update.

If this stuff excites you and you want to try it out, go to the Members section in Settings right now.

Solution 3: Embrace SDR

As mentioned earlier, some users actually prefer SDR. And that’s OK. I think this about more than just the lo-fi aesthetic, and touches on a paradox of photography. Sometimes a less-realistic photo is more engaging.

But aren't photos about capturing reality? If that were true, we would all use pinhole cameras, ensuring we capture everything in sharp focus. If photos were about realism, nobody would shoot black and white film.

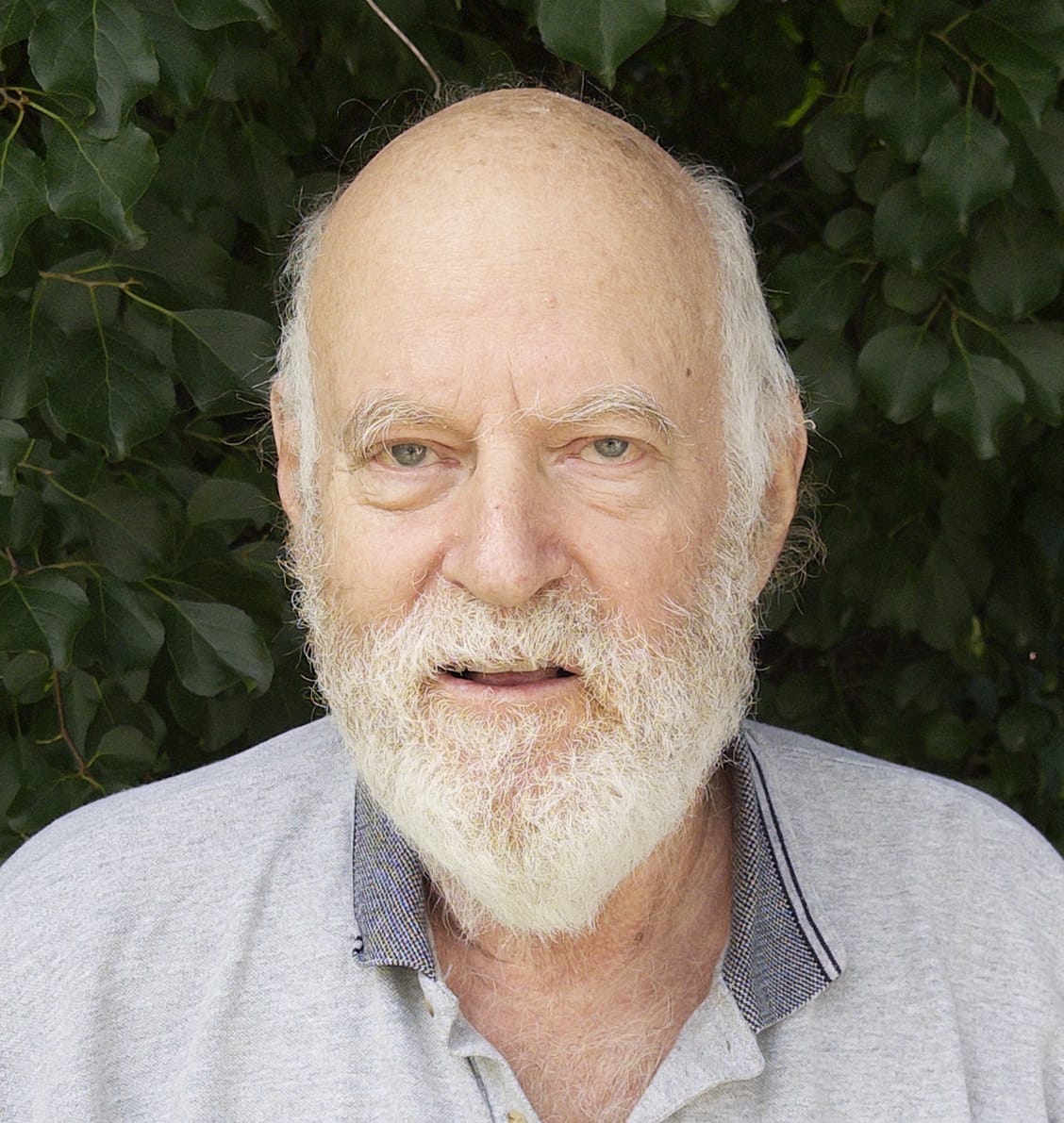

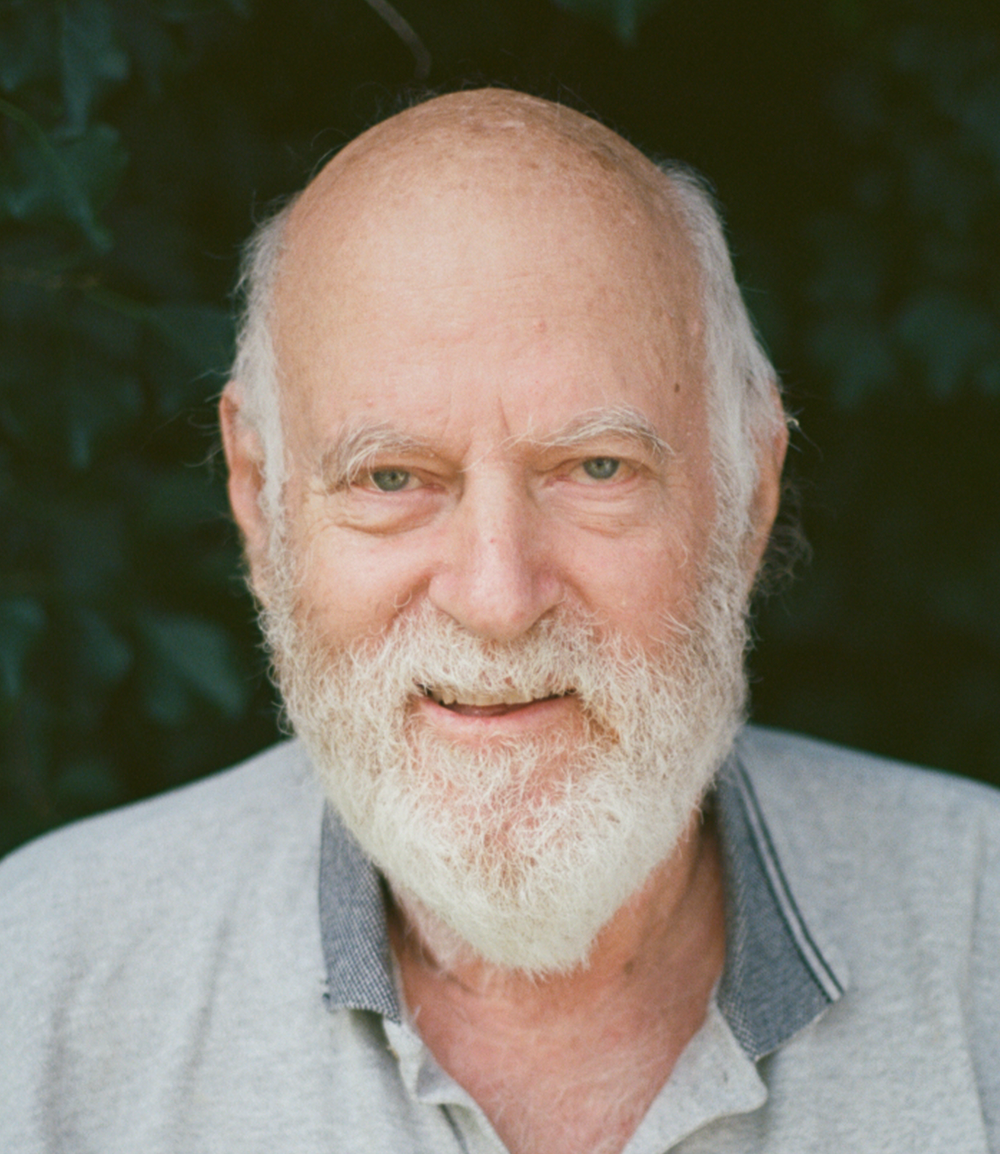

Consider this HDR photo of my dad.

Shot in ProRAW

HDR reveals every wrinkle and pore on his face, and the bright whites in his beard draw too much attention. Just as you might use shallow focus to draw attention on your subject, this is one situation where less dynamic range feels better than hyper-realism. Consider the Process Zero version, with HDR disabled.

While we have plenty of work before Process Zero achieves all of our ambitions, we think dynamic range is a huge factor in recapturing the beauty of analog photography in the digital age.

We think tone mapping is an invaluable tool that dates back hundreds of years. We think HDR displays have amazing potential to create images we've never seen before. We see a future where SDR and HDR live side by side. We want to give you that choice — whether it is tone-mapping, HDR, or any combination thereof. It’s the artists’ choice — and that artist doesn’t have to be an algorithm.

We think the future of sunsets looks bright.